A New Fed Chair—What Matters Most for Investors

Quick Take

The nomination of Kevin Warsh brings renewed focus to Federal Reserve independence, a cornerstone of market confidence that history shows is critical for controlling inflation and maintaining economic stability.

Warsh is an experienced, crisis-tested policymaker whose views have evolved with economic conditions, raising important—but not yet decisive—questions about how he would balance inflation discipline, growth support, and political pressure.

For investors, this leadership change does not alter the long-term investment landscape, as monetary policy is set by committee and well-diversified portfolios are designed to withstand shifts in policy, markets, and economic cycles.

President Trump has announced his nomination of Kevin Warsh to succeed Jerome Powell as Chair of the Federal Reserve when Powell’s term expires later this spring. The decision ends months of speculation, but it opens a far more important discussion—about the future of monetary policy, the independence of the central bank, and what all of this actually means for markets and long-term investors.

Warsh is a familiar figure in Fed circles. He served on the Board of Governors during the global financial crisis. Still, his nomination arrives at a moment of unusual tension between the White House and the Federal Reserve, making context as important as credentials.

Fed Independence: Why Markets Care

The Trump administration has been unusually open in its criticism of the Fed—challenging interest-rate decisions, encouraging investigations of sitting governors, and signaling frustration with monetary restraint. That matters because central bank independence is not a theoretical nicety; it is a hard-earned lesson of economic history.

Countries that allow political pressure to dictate interest-rate policy tend to experience higher inflation, more volatile growth, and less stable financial markets. For decades, the U.S. has benefited from a Fed that can respond to economic conditions—even when doing so is politically inconvenient. Markets don’t require perfection from the Fed, but they do require credibility. The perception that policy decisions are insulated from short-term political goals is central to that credibility.

Kevin Warsh’s Record—and His Evolution

Warsh’s tenure at the Fed from 2006 to 2011 shaped his reputation. In the years following the financial crisis, he argued for tighter policy and less monetary accommodation, expressing concern that prolonged low rates and aggressive asset purchases could distort markets and fuel future inflation. In hindsight, those views may have favored stability over speed, potentially slowing an already weak recovery at the time.

More recently, Warsh has argued that the Fed should move more quickly to cut rates. This shift has drawn scrutiny. One interpretation is that the economic backdrop has changed: inflation has cooled from its post-pandemic peak, growth has moderated, and policy that was once restrictive may now be closer to neutral—or even tight. Another interpretation is more skeptical, suggesting that Warsh’s current stance aligns more closely with the administration that nominated him.

Both readings can coexist. What matters more than labels like “hawk” or “dove” is how Warsh balances inflation credibility with economic support—and whether he demonstrates independence once in office.

Warsh has also been a long-standing critic of quantitative easing and the Fed’s expanding balance sheet. If balance-sheet reduction becomes a priority under his leadership, it could help extinguish remaining inflation pressures, though it would also result in tightening of financial conditions. Reducing the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has proven easier said than done in recent years.

Powell, the Board, and an Open Question

Complicating the transition are ongoing court cases and Department of Justice investigations involving Jerome Powell and Fed Governor Lisa Cook. While Powell’s term as Chair is ending, his term as a governor runs through January 2028. He could choose to remain, though his predecessors—Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen—opted not to.

If Powell steps aside entirely, it would create an additional vacancy, giving the White House more influence over the composition of the Board. That possibility will likely feature prominently in Senate confirmation discussions.

How Have Markets Responded?

The market reaction to Warsh’s nomination has been notable but restrained. He had been on the president’s short list for some time, limiting the element of surprise.

Treasury markets responded with a modest steepening of the yield curve: short-term rates declined while longer-term yields moved higher. Importantly, long-term inflation expectations embedded in bond markets remained relatively stable, suggesting that investors have not lost confidence in the Fed’s ability—or willingness—to control inflation.

The sharpest reaction appeared in precious metals markets. Gold and silver, which had been buoyed by speculative enthusiasm and momentum-driven trading, saw abrupt declines as sentiment shifted. These moves reflected positioning and narrative changes more than a reassessment of long-term inflation risks.

What This Means for Investors

The Fed Chair is one of the most influential economic policymakers in the world, but no chair governs alone. Monetary policy is set by committee, shaped by consensus, and constrained by economic reality.

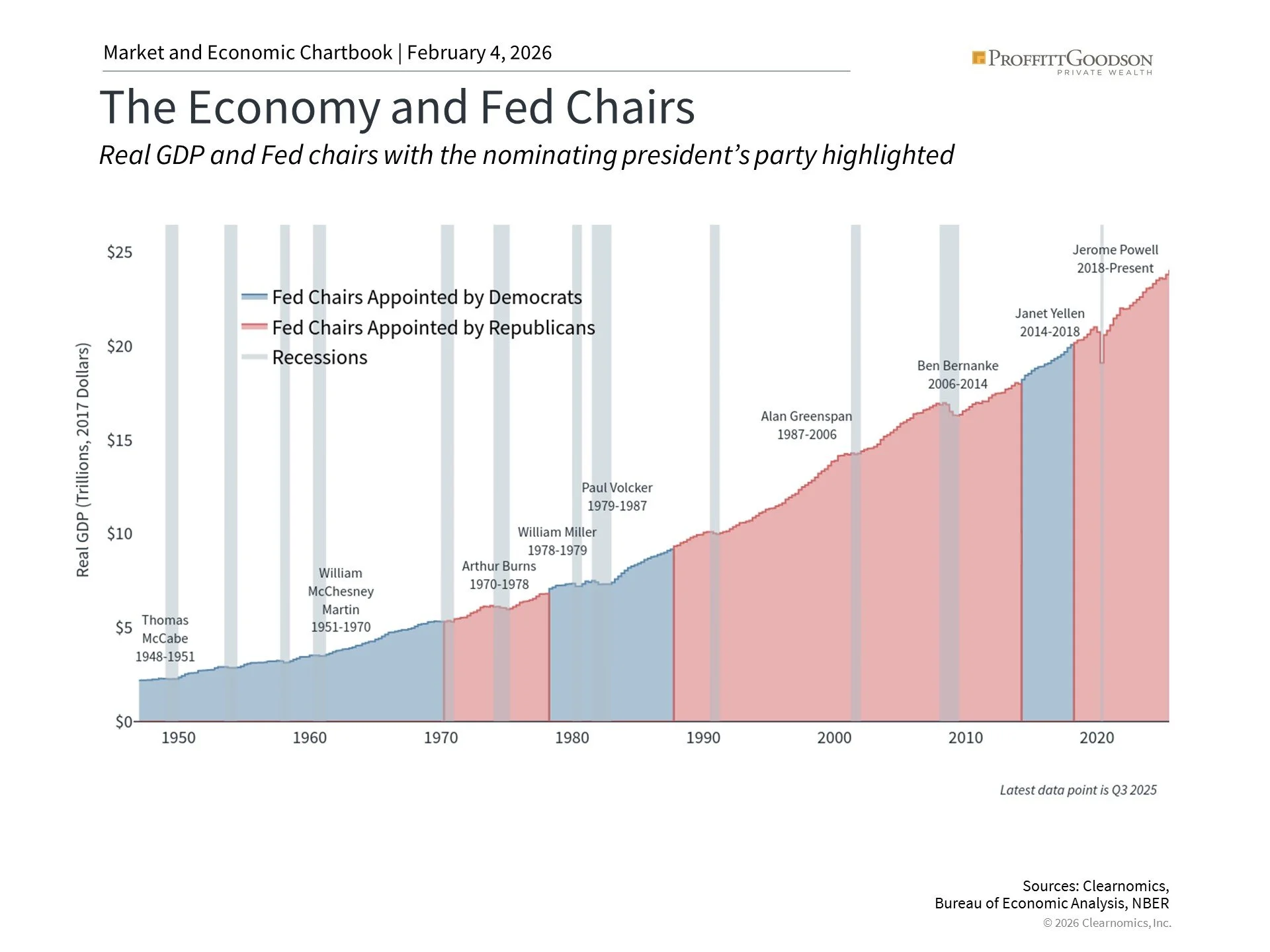

The Federal Reserve has made mistakes—keeping rates too low for too long in the 2000s, and tightening too slowly after the pandemic. Still, over time, it has played a central role in supporting economic growth and financial stability. That track record matters more than any single nomination.

Kevin Warsh is experienced, tested under crisis conditions, and well aware that markets tend to challenge new Fed Chairs at the first hint of stress. Whether he responds with independence and discipline will ultimately define his tenure.

For investors, however, this nomination does not materially change the long-term outlook for the economy or inflation. Well-constructed portfolios are built to endure a wide range of outcomes: higher-than-expected inflation, recessions, market corrections, and policy uncertainty.

Resilience does not come from predicting every turn in the road. It comes from being prepared to travel it—and still arrive at your destination.

Contact us at 865-584-1850 or info@proffittgoodson.com

DISCLOSURES: The information provided in this letter is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation of any particular security, strategy, or investment product, and should not be construed as investment, legal, or tax advice. Proffitt & Goodson, Inc. makes no warranties with regard to the information or results obtained by third parties and its use and disclaims any liability arising out of, or reliance on the information. The information is subject to change and, although based on information that Proffitt & Goodson, Inc. considers reliable, it is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. Source information is obtained from independent financial data suppliers (Interactive Data Corporation, Morningstar, etc.). The Market Categories illustrated in this Financial Market Summary are indexes of specific equity, fixed income, or other categories. An index reflects the underlying securities in a particular selection of securities picked due to a particular type of investment. These indexes account for the reinvestment of dividends and other income but do not account for any transaction, custody, tax, or management fees encountered in real life. To that extent, these index numbers are artificial and cannot be duplicated in real life due to the necessity of paying those transaction, custody, tax, and management fees. Industry and specific sector returns (technology, utilities, etc.) do not account for the reinvestment of dividends or other income. Future events will cause these historical rates of return to be different in the future with the potential for loss as well as profit. Specific indexes may change their definition of particular security types included over time. These indexes reflect investments for a limited period of time and do not reflect performance in different economic or market cycles and are not intended to reflect the actual outcomes of any client of Proffitt & Goodson, Inc. Past performance does not guarantee future results.